Is Betahistine a Strong Antihistamine?

If you’re prescribed betahistine, you might wonder if you’re taking a strong antihistamine similar to common allergy medications like Zyrtec (cetirizine) or Benadryl (diphenhydramine). This confusion makes sense given that betahistine interacts with histamine receptors, but the reality is more complex than it first appears.

The short answer is no – betahistine is not a strong antihistamine in the usual sense. While it does interact with histamine receptors, betahistine dihydrochloride works as a histamine analogue rather than a traditional antihistamine that blocks histamine effects. This key difference explains why betahistine is used to treat vertigo and inner ear disorders rather than allergic reactions.

Understanding these differences is important for patients taking betahistine, as it helps explain why this medication works differently from over-the-counter allergy medicines and why it’s specifically prescribed for vestibular disorders like Ménière’s disease.

What is Betahistine and How Does it Compare to Traditional Antihistamines?

Betahistine is a synthetic histamine analogue developed specifically for treating inner ear disorders and vestibular vertigo. Unlike traditional antihistamines that block histamine receptors throughout your body, betahistine has a unique dual mechanism that sets it apart from regular allergy medications.

Traditional strong antihistamines like diphenhydramine, promethazine, or even newer options like cetirizine work by blocking H1 histamine receptors. This blocking action prevents allergic reactions, reduces inflammation, and often causes drowsiness. These medications are designed to stop histamine from binding to its receptors, which is why they’re effective for treating allergy symptoms.

Betahistine works through a completely different approach. Rather than blocking histamine receptors, it acts as a weak partial agonist at H1 receptors, meaning it actually stimulates these receptors mildly. More importantly, betahistine serves as a strong antagonist at H3 receptors, which are found primarily in your brain and peripheral vestibular system.

This unique receptor profile explains why taking betahistine doesn’t give you the typical antihistamine effects like drowsiness, dry mouth, or relief from allergic reactions. Instead, its primary action targets your inner ear’s blood circulation and your vestibular system’s neurotransmitter balance.

How Betahistine’s Mechanism Differs from Strong Antihistamines

The exact mechanism of betahistine shows why it’s not classified among strong antihistamines used for allergic conditions. Traditional antihistamines work by competitively blocking H1 receptors throughout your body, preventing histamine from causing vasodilation (blood vessel widening), increased vascular permeability, and inflammatory responses that characterize allergic reactions.

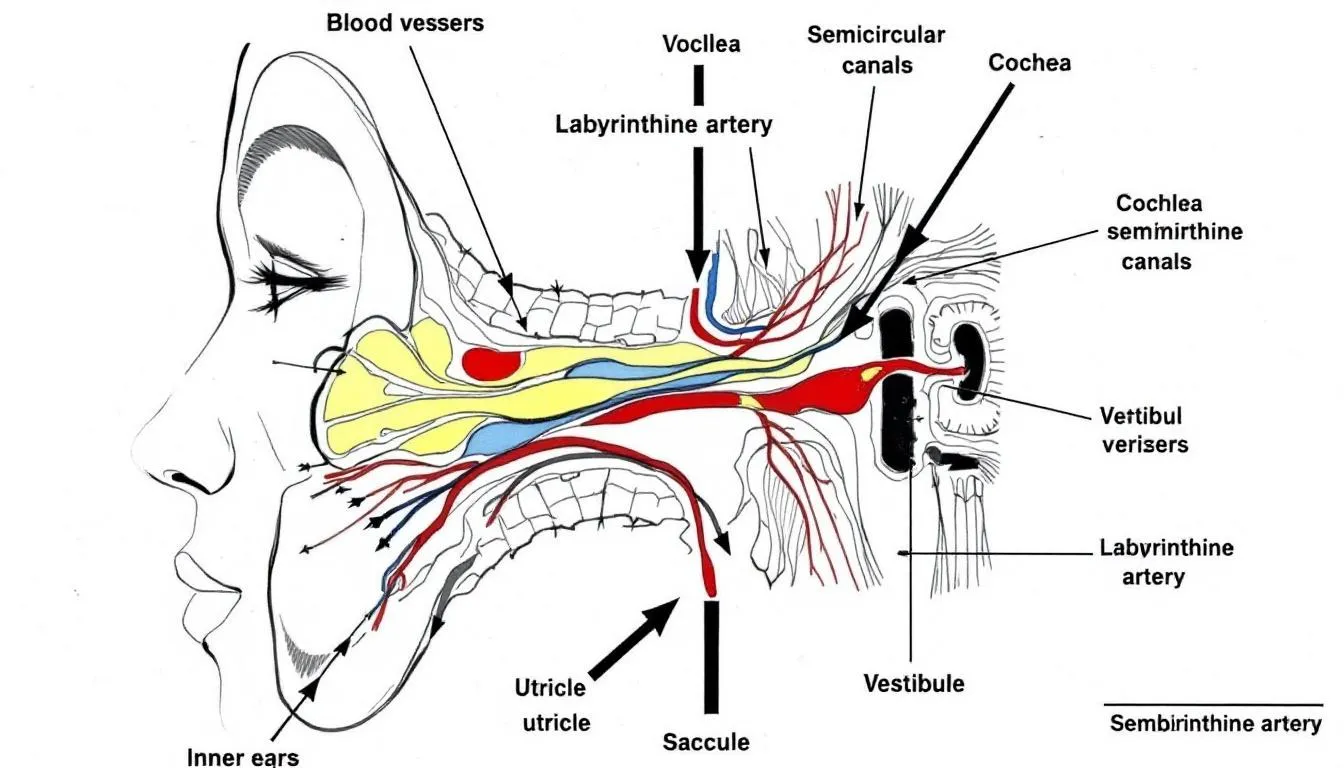

Betahistine’s mechanism operates on different principles entirely. As an H1 receptor agonist in your inner ear, it promotes vasodilation and increases blood flow specifically within the stria vascularis and other blood vessels of your cochlear and vestibular systems. This enhanced blood circulation helps reduce endolymphatic pressure, which is often elevated in conditions like Ménière’s disease.

The medication’s therapeutic effects primarily come from its strong H3 receptor antagonism. H3 receptors function as inhibitory autoreceptors that normally suppress the release of various neurotransmitters including histamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. By blocking these H3 receptors, betahistine increases neurotransmitter release in your brainstem and vestibular nuclei, promoting vestibular compensation after inner ear damage.

This mechanism directly contrasts with strong antihistamines, which broadly suppress histamine activity throughout your body. While traditional antihistamines reduce overall histaminergic signaling, betahistine selectively enhances certain aspects of neurotransmitter function in specific brain regions related to balance and spatial orientation.

Clinical Uses: Inner Ear Disorders vs Allergic Conditions

The clinical applications of betahistine versus strong antihistamines reflect their fundamentally different mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Betahistine is specifically prescribed for treating vestibular disorders, particularly Ménière’s disease, recurrent vertigo, and other inner ear disorders affecting balance and hearing.

Doctors typically prescribe betahistine when you experience:

- Recurrent episodes of spinning sensation or vertigo

- Tinnitus (ringing in your ears)

- Fluctuating hearing loss

- Aural fullness or pressure sensations

- Persistent symptoms related to vestibular dysfunction

The standard betahistine dose is typically 16mg taken three times daily in tablet form, though you may require a lower dose initially. Treatment duration often extends for months, as vestibular compensation and symptom improvement develop gradually over time.

Strong antihistamines serve entirely different clinical purposes. These medications are first-line treatments for:

- Allergic rhinitis and hay fever

- Urticaria (hives) and skin allergies

- Allergic conjunctivitis

- Motion sickness prevention

- Sleep disorders (particularly sedating first-generation types)

- Certain anxiety conditions

The effectiveness of betahistine for different conditions has been well-documented. Clinical trials show significant improvement in approximately 60-70% of patients with Ménière’s disease and vestibular vertigo. However, betahistine shows no proven effectiveness for allergic conditions, as its mechanism doesn’t address the underlying cause of histamine-mediated allergic responses.

Side Effect Profile Comparison

One of the most notable differences between betahistine and strong antihistamines lies in their side effect profiles. This difference directly reflects their distinct mechanisms of action and helps explain why betahistine isn’t considered a strong antihistamine.

Betahistine’s side effects are generally mild and include:

- Mild nausea or upset stomach

- Headache

- Occasional gastrointestinal discomfort

- Rare allergic skin reactions

Importantly, betahistine rarely causes the sedating effects commonly associated with strong antihistamines. If you’re taking betahistine, you typically won’t experience drowsiness, cognitive impairment, or the anticholinergic effects like dry mouth, blurred vision, or urinary retention that frequently occur with traditional antihistamines.

Strong antihistamines, particularly first-generation types like diphenhydramine or promethazine, commonly cause:

- Significant sedation and drowsiness

- Dry mouth and throat

- Blurred vision

- Constipation

- Cognitive impairment and memory issues

- Difficulty with coordination

Even newer, second-generation antihistamines can cause some degree of sedation, though typically less than their predecessors. The absence of these effects with betahistine reflects its selective action on specific histamine receptor subtypes rather than broad histamine blockade throughout your body.

This favorable side effect profile makes betahistine suitable for long-term use in treating chronic vestibular conditions, whereas many strong antihistamines are better suited for short-term use due to their sedating properties.

Effectiveness for Different Conditions

Clinical trials and real-world evidence demonstrate clear differences in effectiveness between betahistine and strong antihistamines across various conditions. Understanding these effectiveness patterns helps clarify why betahistine isn’t classified as a strong antihistamine for general use.

For vestibular disorders, betahistine shows substantial therapeutic effects. The Cochrane Database of systematic reviews indicates that patients with Ménière’s disease and related ear disorders experience significant improvement when taking betahistine compared to placebo. The positive effects include:

- Reduced frequency and severity of vertigo episodes

- Improved balance and spatial orientation

- Decreased tinnitus intensity

- Better overall quality of life scores

- Enhanced vestibular compensation following inner ear damage

The effect of betahistine on your peripheral vestibular system and blood circulation in your inner ear contributes to these therapeutic outcomes. You often notice symptom reduction within weeks of starting treatment, though maximum benefits may take several months to develop.

In contrast, betahistine shows no meaningful effectiveness for conditions typically treated by strong antihistamines. It doesn’t relieve symptoms of allergic reactions, seasonal allergies, or skin conditions like urticaria. This lack of anti-allergic effectiveness further confirms that betahistine doesn’t function as a traditional antihistamine despite its interaction with histamine receptors.

Strong antihistamines excel in their intended applications – treating allergic conditions. Medications like cetirizine, loratadine, and diphenhydramine effectively block histamine-mediated allergic responses but offer no therapeutic value for vestibular disorders or inner ear conditions.

When Betahistine is Prescribed vs Strong Antihistamines

The prescribing patterns for betahistine versus strong antihistamines reflect their distinct therapeutic roles and regulatory status. Understanding when doctors choose each type of medication helps clarify why betahistine isn’t considered a strong antihistamine in clinical practice.

Your physician prescribes betahistine specifically when you present with:

- Diagnosed Ménière’s disease or suspected endolymphatic hydrops

- Unexplained recurrent vertigo episodes

- Balance disorders affecting your daily activities

- Tinnitus associated with inner ear dysfunction

- Hearing loss fluctuations suggesting vestibular involvement

Betahistine requires a prescription in most countries and is often used as part of comprehensive treatment plans that may include physical therapy, dietary modifications, and lifestyle changes. The medication is widely available in Europe, Canada, and Asia, though it lacks FDA approval in the United States, where it’s available through compounding pharmacies.

Treatment with betahistine typically involves long-term use, often continuing for months or even years to maintain symptom control and support ongoing vestibular compensation. Your doctor may adjust your dose based on your response and tolerability.

Strong antihistamines follow different prescribing patterns:

- Many are available over-the-counter for self-treatment of allergies

- Prescription varieties are used for severe allergic conditions

- Treatment duration is typically short-term for acute symptoms

- Used as needed for seasonal allergies or specific triggers

Your underlying condition being treated determines medication choice. For vestibular symptoms, betahistine targets the specific pathophysiology of inner ear disorders. For allergic reactions, traditional antihistamines address histamine-mediated inflammatory responses throughout your body.

This distinction in prescribing patterns reinforces that betahistine, while interacting with histamine receptors, functions differently from strong antihistamines and serves a specialized role in treating ear disorders and vestibular vertigo.

Key Takeaways About Betahistine and Antihistamines

Understanding whether betahistine qualifies as a strong antihistamine requires recognizing the fundamental differences in mechanism, clinical use, and therapeutic effects between these medication types. While betahistine does interact with histamine receptors, its unique profile as a histamine analogue sets it apart from conventional antihistamines.

The evidence clearly shows that betahistine is not a strong antihistamine in the traditional sense. Its weak H1 receptor agonist activity combined with strong H3 receptor antagonism creates a specialized therapeutic profile focused on treating vestibular disorders rather than allergic conditions. This mechanism explains why you don’t experience typical antihistamine effects like sedation or allergy relief when taking betahistine.

For patients prescribed betahistine, this understanding helps set appropriate expectations about your medication’s effects and duration of treatment. Unlike strong antihistamines that provide relatively quick relief from allergic symptoms, betahistine requires patience as it gradually improves vestibular function and reduces vertigo symptoms over weeks to months.

If you’re taking betahistine or considering it as a treatment option, discuss your specific symptoms and medical history with your doctor. They can explain how betahistine might help your particular condition and whether it’s the most appropriate treatment choice among the various medicines available for treating vertigo and other ear disorders.

Remember that while betahistine is generally well-tolerated, it’s important to take it as prescribed and report any persistent symptoms or concerns to your healthcare provider. Understanding your medication helps ensure the best possible treatment outcomes for your underlying condition.